Recently, we’ve been seeing a lot of hype about citizen reporting with mobile phones during elections. It is often conflated with the term “election monitoring,” but this does a disservice to both citizen reporting and election monitoring, a discipline and field that has been around for some 20 years. These two approaches have markedly different goals, target audiences, and processes. We think it is time for readers to definitively understand what election monitoring is in contrast to citizen reporting, and what the role of mobile phone and mapping platforms are in regard to these two very different forms of engagement during elections. We aim to clearly differentiate between them once and for all.

We also urge the adoption of differing terms - citizen reporting during an election versus systematic election monitoring. Mobile phones, SMS, and mapping platforms play a role in both citizen reporting and election monitoring, of course.

We believe that more clearly distinguishing between citizen reporting during an election and the discipline of systematic election monitoring will better serve organizations that are considering using mobile technology for either of these engagement processes.

Ensuring the Validity and Fairness of an Election: What is Election Monitoring?

Election monitoring is a long-standing and established discipline with a particular methodology going back decades -- long before the advent of wide-spread mobile technology. Election monitoring aims to assess the conduct of an election process on the basis of established standards. Monitors, often domestic monitors from local coalitions within a given country, record and report such instances. According to the National Democratic Institute, a technical assistance organization to domestic election monitoring efforts, election monitoring has specific goals, especially during transitional elections:

Particularly significant in the context of transition elections is the role monitors play in reassuring a skeptical public about the importance of the electoral process and the relevance of each voter's participation. Often in these environments, the public's only experience with politics concerns human rights abuses, fraudulent elections and military or autocratic rule. In these circumstances, basic notions of civic responsibility need reinforcement, and anxieties must be overcome.

Publicity surrounding the formation of a monitoring operation, coupled with the pre-election activities of monitors and their presence at voting stations on election day, enhances public confidence and encourages citizen involvement in the process. Public statements and reports issued by the monitoring group may lead to changes in policies that promote a more equitable election process. Through the use of mediating techniques, monitors may help resolve disputes that emerge during the campaign period. Their presence at polling sites deters fraud, irregularities and innocent administrative mistakes. Deployment of election monitors to troubled areas also serves to discourage intimidation during a campaign and on election day. In addition, when observers monitor the vote counting process through an independent vote tabulation or other means, they provide an unbiased source for verifying official results.

Finally, a post-election evaluation conducted by an independent monitoring group may also influence the positions of electoral contestants regarding the overall legitimacy of the process. A relatively positive assessment should encourage acceptance of the results by all parties. By contrast, a negative critique may lead to rejection of the results if the process is deemed illegitimate.

Election monitoring, as a term, has, as of late, sometimes been replaced by the term "election observation" to connote that it is necessary, especially during transitional elections, to work on the entire electoral process over a longer period of time, rather than focus on election-day proceedings only.

In short, according to the National Democratic Institute’s (NDI) election guide “How Domestic Organizations Monitor Elections, "election monitoring aims to create a trusted source that can pass judgment on the validity and fairness of the election. ”

How Are Mobile Phones Used in Systematic Election Monitoring?

As noted, election monitoring follows a standard protocol – trained volunteer election monitors are deployed to a select number of polling stations on election day. There are four different deployment methodologies for election monitors, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The point is that the methodology that a given election monitoring organization chooses is strategic and suited to the information that it wants to get back.

Observers can be equipped with mobile phones to report on the conduct of an election in this systematic assessment of the election protocol and any deviations. The election monitors record information from their polling station a number of times during the day, and transmit that data to centralized databases via SMS or voice messages. The systemtic way in which the data is gathered (again, by domestic trained election volunteers) allows the monitoring organizations to draw conclusions about the legitimacy and accuracy of the election.

Ian Schuler, author of “SMS as a Tool in Election Observation,” described how the SMS system worked during election monitoring in Sierra Leone:

Observers used a series of carefully constructed codes to send short message system (SMS) messages to one of seven phones connected to a computer by USB cables at NEW [the domestic election coalition] headquarters. NEW observers could transmit complex information about the election, from minor procedural infractions to serious flaws. The computer then interpreted the codes and stored the information in a database, which included reports that facilitated rapid analysis of the data.

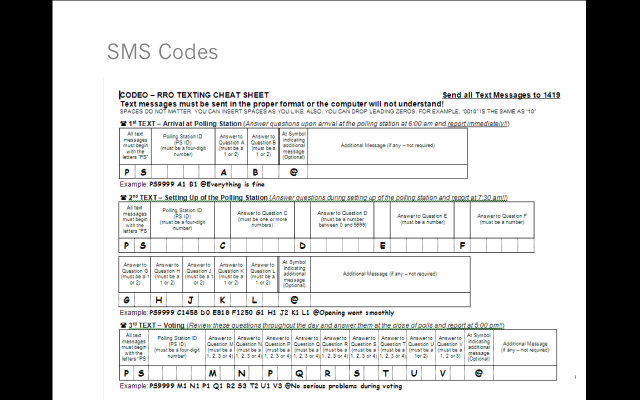

To show the systematic nature of the data collection during an election monitoring effort, we've pulled some images from a recent presentation of election expert Richard Klein from NDI during an event we recently held on the topic in Washington, DC.

The first image shows the level of detailed reporting required for systematic election monitoring. Submitters must report using various codes. Here's a look at the SMS codes used during the 2008 Ghanaian election.

An SMS that covers all this information will look like this when sent in to a centralized database. SMS like this are sent from thousands of trained volunteers who are at a specific, randomly chosen polling station all day at four or five different times during the day. This is resulting in tens of thousands of messages with significant data that can be evaluated and assessed by the domestic election monitoring coalition in a given country.

Citizen Reporting: Impressions and Engagement

Citizen reporting to platforms like Ushahidi, in contrast, provide untrained citizens with a medium on which to share their subjective election experiences. This kind of information is useful to provide an impression of an election as experienced by voters and is a way to engage citizens in the election and manifest those impresssions visually in close-to-real time.

However, it is not the same as the large-scale, multi-level process of election monitoring. Citizen reporting is not representative or standardized and thus can not serve as a trusted source about the conduct, validity or fairness of an election. That said, enaging citizens in an election could theoretically be useful and interesting. However, in reality to date, the actual numbers of engaged citizens that are reporting on their experiences during election day have been too small to have much, if any, impact.

We will go into more detail of some of these numbers of several of recent election citizen reporting instances below, and contrast them with reporting data from systematic election monitoring, where possible.

The Crucial Difference

In a February interview with MobileActive.org, Schuler discussed the difference between systematic election monitoring and citizen reporting:

Citizen reporting is a great exercise. It is important for citizens to have an outlet for their voices that those sort of exercises can really collect – it’s really good [for sharing] experiences and information about what’s going on. But it’s a different exercise than election observation or election monitoring, which has the goal of really evaluating the process. In election monitoring, a group of citizens come together well in advance of an election and develop a systematic and valid strategy that employs a number of different approaches for evaluating ‘was this a good process or not’ and informing the public about to what extent it was a good process and to what extent there were problems.

Election observation is a method used to deter fraud, to inform citizens about what actually happened during an election, and to allow citizens to decide if the process was fair. Election observation depends on trained observers who evaluate voting practices – everything from guarding against pre-election intimidation tactics that could influence voter turnout, to checking for ballot stuffing, to ensuring that all voters vote only once and for the candidate they intended.

In contracts, citizen reporting is based on sentiment and in-the-moment impressions from citizens. Citizen reporting is not meant to be a means of judgment about the quality or conduct of an election, but rather a source of on-the-ground impressions from voters and as a way to engaged them.

What Does the Reality Look Like? A Hard Look At The Numbers (aka: The Smackdown between Election Monitoring and Citizen Reporting)

There is a marked difference between election monitoring and some of the more well-publicized cases of citizen reporting when one takes a close look at the numbers. A recent citizen reporting effort in Sudan, the Sudan Vote Monitor, which ran on the Ushahidi platform and was supported by senior officials from the US State Department, estimated that they received between 300 and 500 responses during the recent elections. In comparison, two domestic election monitoring coalitions, SuGDE and SuNDE, “received more than 13,500 reports from over 4,300 trained and accredited election observers who were deployed to over 2,000 polling stations across all of Sudan’s 25 states.” SuNDE and SuGDE decided not to use SMS to report data as they rightly feared that the mobile networks would be shut down during the election. The networks were indeed not operational for much of the election proceedings.

In Lebanon’s 2009 elections, LADE, the Lebanon domestic election monitoring coalition, deployed 2,500 volunteer citizen observers throughout the country at 5181 polling stations; each volunteer submitted five SMS updates through the day, resulting in roughly 12,500 reports. During the same Lebanese election period, the citizen reporting instance of Ushahidi, Sharek 961, received 26 SMS submissions, 209 web submissions, and 1031 Twitter responses.

In Ghana, more than 4,000 election observers were deployed by CODEO, the Coalition of Domestic Election Observers. There was no citizen reporting instance in Ghana. Compare that to Vote Report India, an Ushahidi instance for citizen reporting during the recent Indian elections (a country of more than 1 billion people) that received about 200 reports. Cuidemos el Voto, also running on Ushahidi in Mexico, received 11 SMS submissions, 289 web submissions, and 34 Twitter submissions.

Even though these citizen reporting numbers are exceedingly poor, this isn’t to say that citizen reporting during elections is a bad idea. Platforms like Ushahidi for mobile and online reporting give citizens a way to share and broadcast their experiences that they may not otherwise have had. However, it would behove commentators to take into consideration more rigorously what each engagement process is designed to deliver - and take a hard look at the reality (and poor performance to date) of citizen reporting during elections.

In short, conflating the terms “election monitoring” with “citizen reporting” is problematic. Citizen reporting (via SMS and online) during elections has so far received relatively low response rates compared to established election monitoring systems, yet have been hyped as the solution to election corruption and disruption.

Commentators fall into two traps: 1. they do not understand election monitoring as a discipline (and have been too lazy to learn) and 2. consider new technology unilaterly as 'cool' with technology that gives a voice to citizens considered good and useful. We can wholheartedly agree with the second point but are also concerned that the hype over citizen reporting and public mapping during elections distorts the issues and distracts from how domestic coalitions are using mobile phones already (and for years) in novel, large-scale ways for systematic monitoring, all the while focusing on efforts that have such low participation numbers to be essentially inconsequential even as a way for citizen engagement.

The Use of Mapping Platforms in Citizen Reporting and Election Monitoring

While we encourage a more disciplined approach to differentiating between the goals and impact of citizen reporting versus systematic election monitoring, we are also keenly interested in the use of mapping platforms to visually map data from either efforts. We recently conducted a comparison between two such mapping and data-aggregation platforms that have been used in elections, Ushahidi and Managing News.

As we note in the review, Ushahidi, a platform for map- and time-based visualizations of incoming reports, has been used most prominently in crisis mapping and citizen reporting. The first instance of Ushahidi tracked the post-election violence in Kenya in 2007, closely followed by an instance covering outbreaks of xenophobic violence in South Africa in early 2008. Numerous Ushahidi instances around elections were deployed in India, Lebanon, Mexico, Sudan, and other countries, most, as we noted, with relatively few submisisons.

DevelopmentSeed's Managing News, another mapping platform, originated as a news aggregation and republishing platform, but also offers SMS and mapping functionality. It's been used to visualize election results in Afghanistan, monitor security-related news reports in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and track incidences and reports of H1N1 in the United States. Managing News is based on the open-source content management system Drupal, and makes extensive use of existing modules, as well as related open source projects for SMS and mapping.

Typically, mapping platforms like Ushahidi have not been used in systematic election monitoring efforts for a number of reasons; the most crucial of which is that many domestic coalitions rightly believe that close-to real-time mapping in sensitive elections is not advisable until incoming data from election monitors has been verified and there are enough reports to demonstrate veracity and even statistical significance. During transitional elections in particular, tensions can run high and domestic coalitions, as independent and unbiased entities, have to manage information flow and combat rumors and misinformation until their data is reliable and verified.

But even where election monitoring organizations are interested in publishing live data, that isn't the priority. The priority is aggregating information over the entire country and smaller geographic areas and Ushahidi, to date, just isn't built for this. Managing News, by contrast, has allowed some organizations like NDI, to collect "apples-to-apples", structured information about polling stations and has allowed them to both drill down and sum up the information to get a better idea of what happened around the country.

In Sum

While citizen reporting during elections is valuable because it gives a voice to people who want to draw attention to their experiences, it is not a substitute for, nor comparable to, systematic election monitoring. Election monitoring is done by local, domestic observers, builds ongoing organizational capacity, and, most importantly, helps a population determine whether to trust the results of an election. We do wonder, given the low participation numbers in citizen reporting during elections to date, whether citizen reporting warrants the hype - and whether new products can live up to their promise to truly engage a citizenry.

Katrin Verclas is the director of MobileActive.org. Follow her on twitter at @katrinskaya. Anne-Ryan Heatwole is a writer for MobileActive.org. Follow her on Twitter at @arheatwole

Photo credit: Katrin Verclas

| Cutting Through the Hype: Why Citizen Reporting Isn't Election Monitoring data sheet 8576 Views | |

|---|---|

| Countries: | Albania Ghana India Lebanon Mexico Montenegro Sudan |

Anyone knows on Zimbabwe?

Very good analysis.

I rmember there had been use of cell^phones to report poll stations data in Zimbabwe last elections, does anyone knows details?

citizen reporting

Great post!

Our grassroots micro reporting platform herMe! (available on iPhone and Android, Symbian to follow soon) is a perfect match for both applications:the more free style "citizen reporting" and the more formal way of "trusted election monitoring". As a unified platform, hereMe! will enable and enhance the communication and discussions at every level. Citizens can e.g. immediately express their comments on formal election monitoring, they can vote on the noteworthyness and so on.

Take a look at www.myhereme.com for more information.

very surprised

wait, are you saying someone was wrong at the State Department? How could that possibly happen?

Armenia / Georgia

Thanks for the post. Plenty to think about and I don't doubt all of the points you raise. However, in the case of countries such as Armenia, I think they don't necessarily always apply. For example, after the past few elections, the population in general doesn't trust either the electoral system or the election observers, local or international.

That said, we need those election observation organizations anyway, as we need something to compare the declared results with a more neutral source of information than actual political parties with a reason to either declare the vote valid or invalid. We also need a system which doesn't allowed unverified reports from being taken as fact. So, I can't help but wonder if what we're missing is the potential for online tools such as Ushahidi to be a kind of 'clearing house.'

That is, it's a tool that obviously has more worth and credibility in the hands of trained election observers, but it could also be a way for others to report violations to those observers for eventual verification. In fact, this happens anyway, but via telephone and word of mouth, but by the time observers are informed and on the scene to check claims of illegalities 30-60 minutes or longer have passed.

As long as there is a way to filter or mark citizen reports, and as long as there is a way to verify them, couldn't software tools help? Like I said, this is happening anyway, with reports going through by phone. The problem is that observers get there too late to check whether such reports are true or false. Ironically, in the case of countries such as Armenia, it is often said jokingly that violations rarely happen with international observers are present.

Branded vehicles (usually flash 4-wheel drives often with OSCE emblazoned over them), kind of warn off those committing violations to wait until they're gone. Moreover, domestic observation is often flawed because some are scared off, bribed or not as well trained as their international counterparts. Basically, all forms of election observation and monitoring are flawed to some extent so I can't but wonder if a holistic system, with the necessary safeguards, isn't an option.

Anyway, am still thinking that election mapping has a place, but have always considered it one to be used by trained professionals. This weekend, for example, one was deployed in Georgia for the local elections by NDI, Transparency etc. Would be interested to hear what you think:

http://elections.transparency.ge/

Post new comment